Collaborative Therapy With Multi-Stressed Families: From Old Problems to New Futures

WILLIAM C. MADSEN PH.D

Family Institute of Cambridge, 51 Kondazian Street, Watertown, MA 02172

(617) 868-9044 phone (617) 497-6850 fax

E-mail: madsen1@mediaone.net

CHAPTER 2: WHAT WE SEE IS WHAT WE GET: RE-EXAMINING OUR ASSESSMENT PROCESS

In most agencies the need for assessments is a taken-for-granted fact of life. Many programs separate out a distinct assessment phase of treatment. However, the process of conducting an assessment is also a profound intervention. Consider Jeffrey, a 14-year-old boy who has been hospitalized 12 times in the last 3 years. At his most recent psychiatric admission, an intake worker is collecting his previous hospitalization history. As the worker methodically obtains the details of precipitant, treatment course, and discharge plan for each hospitalization, he notices Jeffrey’s presence in the room increasingly shrinking. The intake worker is only collecting information, not “intervening,” and yet is it any wonder that by the time Jeffrey describes his 11th unsuccessful hospitalization, his sense of self has shrunk to microscopic level? The questions we ask in an assessment not only collect information but also generate experience. The process of answering those questions shape clients’ experience of self and powerfully affect how subsequent work unfolds. This chapter critically examines the effects of our conceptual formulations on clients and the process of therapy. It offers a conceptual map for thinking about family difficulties in non-blaming, non-shaming ways and outlines a collaborative assessment process that promotes particular attention to family knowledge, abilities, and resourcefulness.

EXAMINING THE EFFECTS OF OUR ASSUMPTIONS

In the first chapter, Linda (the client who was described in some detail) encountered two different mental health teams. The first team viewed Linda as a help-rejecting borderline with inappropriate boundaries, whereas the second team saw her as a survivor of serious abuse who was desperate for help but very suspicious due to a long history of previous negative experiences with helpers. As we reflect on Linda’s interactions with the two different teams, several important points emerge. Different observers “see” different things in a situation. Perception is not a passive process of observation but an active drawing of distinctions (Tomm, 1992). The distinctions we draw as therapists are profoundly organized by our conceptual models, our own history, the institutional contexts in which we work, and broader cultural assumptions that shape our interpretation of the world. The different views of Linda and the problems in her life were shaped by the context of the respective teams’ interactions with Linda and the clinical orientations within which those interactions were interpreted. The first team operated within a medically-oriented outpatient clinic in which Linda felt very uncomfortable. Their work was organized by an assumption that treatment must begin with a thorough diagnostic assessment. This assumption encouraged a particular set of questions and organized a particular relational stance with Linda. The second team saw Linda in her own home, and while they valued the importance of clearly understanding situations, they organized their work around an assumption that therapy must begin with a compassionate connection. That different priority positioned them in a different relational stance with Linda. In turn, Linda interacted quite differently on her own turf than on professional turf and the different organizing assumptions encouraged the respective clinicians to draw quite different conclusions about those interactions.

Our distinctions promote selective attention to particular events and inattention to others. Those distinctions organize our experience of what we are observing. The respective stories about Linda influenced the various responses to her. The first team anticipated her outbursts and described themselves as stiffening up in anticipation of Linda’s “inappropriateness.” The second team, whose perspective emphasized her resilience and commitment to her children, had a different reaction to Linda. They admired her persistence in continuing to seek out help and wanted to help her have a different experience in their interactions with her.

Our formulations about clients position us in particular relationships with them. Our reactions to them are often communicated in subtle ways and, in turn, invite client reactions that develop into repetitive interactions. For example, Linda thought the first clinical team was uneasy around her, perceived them as critical of her, and viewed them as “uptight and judgmental.” She responded with suspiciousness and defensiveness, and an interaction developed that was characterized by mutual mistrust, blaming, and antagonism. As the interaction became more polarized, each party became more entrenched in their negative view of the other. In contrast, Linda felt understood and validated by the second team and responded with “more appropriate” behavior with them. Although she had a fiery temper and reacted strongly to perceived slights, she also recovered quicker and the interactions between the second team and Linda were largely characterized by mutual appreciation. Their respective views of each other led to a more constructive interaction. Our formulations have strong effects on our views of clients, on clients’ views of us, and on our developing relationships.

If we accept this premise, it makes sense that we need to be conscious about how we choose to view clients, understand problems, and organize our work. The questions we ask and the ways in which we organize the information we receive have a profound effect on our subsequent work. At the same time, it is important to not simply view this process in a strictly linear fashion. Clients’ actions organize helpers’ views of them. Helpers’ views of clients organize what they attend to while relating to clients. There is a recursive interaction between the two. Because we have a degree of control over our attention, we can decide to attend to things that will be most constructive and therapeutic. Our conceptual frameworks can highlight the similarities between clients and us and humanize our relationship with them or they can highlight our dissimilarities, objectify clients, and invite us to treat them as “other.” These interactions have the potential to invite the enactment of particular life stories for clients. If we use pathologizing categories to understand families, we run the risk of bringing forth pathology. Conversely, if we use categories that highlight clients’ resourcefulness, we increase the chance of bringing forth competence. In short, what we see shapes what we get and where we stand shapes what we see.

EXAMINING THE CONTEXT OF OUR ASSUMPTIONS

Our views of clients are embedded in and profoundly shaped by taken-for-granted professional and cultural assumptions about clients, problems, and the process of therapy. For example, treatment traditionally proceeds through a process of conducting an assessment, developing a treatment plan, and implementing a set of interventions organized by that treatment plan. This process is anchored in a number of assumptions. It begins with an assumption that a client’s condition can be “objectively” studied and identified in order to treat it. This assumption itself is embedded within a broader assumption that “reality” is knowable and its elements can be accurately and reliably discovered and described, and that the observer who is describing it stands outside the observed system. These assumptions are anchored in a set of beliefs about reality that reflect a modernist world view. Kathy Weingarten (1998) has concisely summarized the implications of a modernist approach for family therapy:

“Within family therapy, a modernist approach entails the observation of persons in order to compare their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors against preexisting, normative criteria. The modernist therapist then uses explanations, advice, or planned interventions as a means to bring persons’ responses in line with these criteria” (pp. 3-4).

This process of entering into a family system, observing how it functions, comparing that to our theories of “appropriate” behavior and then developing a series of interventions to tinker with the system so that it functions more “appropriately” puts us in a particular relational stance with families. It positions us as an outsider acting on the system. This stance may provoke a response from families that don’t particularly appreciate the experience of being acted upon. We may interpret their response through our perspective as “resistance” or “noncompliance,” leading us to either pathologize or try to counter that response. (Chapter 3 examines this process in more depth.)

As described in the previous chapter, it is helpful for both pragmatic and aesthetic reasons to position our selves as insiders working with families rather than outsiders acting on them. In my own efforts to develop conceptual models and clinical practices that fit with a relational stance of an appreciative ally, I have been drawn to narrative, social constructionist, and postmodernist ideas. These ideas can be both frustratingly abstruse and wonderfully liberating. They offer a way of thinking about clients and interacting with clients that allow us to bring more of ourselves into our work and position ourselves in ways that clients seem to find very helpful. Much of the material in this book is profoundly influenced by narrative, social constructionist, and postmodernist ideas. At the same time, I also describe ideas that reflect my original grounding in modernist approaches to family therapy. In attempting to draw from both world views, I am not striving for conceptual purity but rather utility. Even though my work is largely anchored in a postmodern worldview, I want to acknowledge and honor both my own history and much of the field’s history.

I am not going to describe postmodernist, social constructionist or narrative world views in great depth in this book. Instead, I will try to avoid off-putting jargon and yet bring to life the rich possibilities of these ideas through concrete applications. Social constructionist inquiry focuses on the processes by which people come to describe, explain, and account for the world and their position in it (Gergen, 1985). Social constructionist ideas are embedded in a postmodern world view in which there are no essential truths and in which the therapist is no longer the expert who knows how families should solve their problems. Rather than developing a series of interventions designed to bring clients in line with normative standards, the therapist is, in the words of Kathy Weingarten (1998), a “fellow traveler,” listening carefully and participating in conversations that generate many possible ways forward. Anchored in a lateral relationship in which our thinking is made visible to clients, there is an attempt to honor clients’ abilities to develop solutions and move forward in their lives and to draw on their immediate experience as the criterion against which we measure our efforts rather than normative models. This world view fits well with a relational stance of an appreciative ally.

A social constructionist conception of the self can be helpful in thinking about the effects of our conceptual frameworks on clients. Many individual psychology models assume that what we call the “self” consists of innate personality characteristics that represent the true essence of the person (e.g., Linda is a “borderline”). These models often take an ahistorical, acontextual approach that isolates individuals from their social context. Social constructionist approaches view the “self” as constructed in social interaction (e.g. Linda would become very different women in different cultures and different historical periods). Our ways of understanding ourselves and our relationship to the world develop in the course of our interactions in the world and are profoundly shaped by those interactions. We are continually creating our identities in the moment as we interact with others. This perspective shifts the focus from “who we are” (as a pre-existing quality) to “how we are” (our ways of being that are continually being reinvented). However, the person we are becoming is profoundly shaped by and inseparable from our social context.

We grow up in a world of conversations, some involving us, some simply about us. These external conversations become internalized and begin to comprise the stories we tell about ourselves (Tomm, 1992). For example, Linda has heard all her life that she was “a good for nothing, out of control bitch who was going nowhere in her life.” She heard it from her family, from various boyfriends, and from a culture in which outspoken, assertive women often come to be labeled strident or a “bitch.” Over time, those conversations become internalized and operate as a framework for making sense of her life. The conversations that helpers have with and about clients contribute to the construction of their identities and experiences of self. The Linda who interacted with the second team was a different woman from the Linda who interacted with the first team. In the course of her interactions in each context, Linda and the two teams shaped her respective identities. This process occurs in and is profoundly influenced by the broader socio-cultural context of those interactions. This assumption that the self is constructed in social interaction rather than pre-existing can be perplexing and challenging. The claims of social constructionism violate fundamental cultural assumptions. However, they provide a useful guideline for approaching clients. If we assume that our conversations about and with clients have important effects on how they become in their lives, it behooves us to think carefully about how we organize both our internal conversations about clients and the external dialogues we have with them.

Our conceptual models organize our internal conversations about clients. We can think about these conversations as the stories we develop about clients in the course of interacting with them. The stories that we carry with us organize what we see and shape how we react in our interactions with clients. It is inevitable that we develop such stories in our interactions with clients and it is inevitable that those stories have a profound effect on us, on clients, and on our relationship. Given this, we can attempt to develop conceptual models (or professional stories about clients, problems and therapy) that will have the most useful effects. From a social constructionist perspective, our hypotheses or formulations can be seen as stories we are creating in the course of our interactions with families to organize our work. Within this perspective, it is particularly important to think about the effects of the formulations we are developing. The following questions provide criteria for evaluating the effects of our formulations:

- What are the effects of our formulations on our view of clients?

- What are the effects of our formulations on clients’ views of themselves?

- What are the effects of our formulations on our relationships with clients?

- Do our formulations invite connection, respectful curiosity, openness and hope?

- Do our formulations encourage the enactment of our preferred relational stance with clients?

In an attempt to be sensitive to the effects of our formulations on the relationship we develop with clients, this chapter highlights ways of understanding problems that are non-blaming and non-shaming and that pay particular attention to family wisdom and competence. The concept of constraints provides one foundation for a new way of conceptualizing families and problems.

FROM DISCOVERING CAUSES TO IDENTIFYING CONSTRAINTS

Many of our attempts to understand situations involve a search for causality (e.g. Why did X happen?). Another way of attempting to understand a situation draws on the concept of constraints (e.g. What prevented something other than X from happening?). When applied to problems in life, the concept of constraints shifts the organizing question from What caused the problem? to What constrains an individual or family from living differently? We can identify constraints at a number of levels, including a biological level, an individual level, a family level (which includes family of origin), a social network level (which includes helpers as well as neighbors, friends and relevant others), and a socio-cultural level (the taken-for-granted cultural assumptions that organize our sense of self and the world around us). At each level, we can examine those factors that constrain people from addressing a problem differently. The following example highlights constraints across multiple levels.

CONSTRAINTS ACROSS LEVELS

Charlie is a hyperactive, 7-year-old boy in foster care who was removed from his home 3 years ago for neglect. Both biological parents currently have no contact with him. For the past year, he has lived with his second foster mother and father, Maria and Joey, a childless couple who hope to adopt him. He has been referred for therapy by Maria for help with his attentional and behavioral difficulties. When he is alone with his foster parents, he does fine. However, at school and when they visit Maria’s large family, Charlie becomes scared and out of control and ends up fighting with other children. His foster parents, who normally are nurturing, firm and consistent, become tentative with him, alternately pleading and threatening. Charlie recently disclosed being sexually abused by an older sibling in his previous foster home which held a total of eight natural and foster children. His disclosure has prompted a crisis for Maria who was willing to take in any child except one who was sexually abused and who now feels trapped by discovering Charlie was abused after growing so attached to him. She fears that the abuse has scarred Charlie for life and yet is in great conflict with the school who she sees as scapegoating him after they were told by his protective worker, Pam, that he had been sexually abused. Maria feels little support from Pam whose office is a great distance away and feels very alone in now dealing with Charlie’s disclosure.

If we pose the question of what constrains Charlie from better managing his behavior, we can identify constraints at a number of levels. Charlie does fine in a small, structured setting. However, in larger chaotic situations, he loses his focus and becomes fearful and easily distracted, and his behavior becomes unmanageable. At a biological level, attentional difficulties may constrain him from more effectively organizing the myriad stimuli impinging upon him. Perhaps, Ritalin or another medicine would help bolster his ability to manage chaos.

At an individual level, Charlie states that “he can’t trust adults.” This belief, anchored in his traumatic experiences of being neglected by his biological parents and abused in his first foster home, constrains his ability to turn to Maria and Joey for support when he feels overwhelmed. The lack of support and resulting sense of isolation leaves him even more vulnerable to the disorganizing effects of chaos at school and when he visits Maria’s large family. In this way, the effects of trauma may further constrain his ability to manage his behavior in less structured settings.

At a family level, we can identify a number of interactional constraints that hinder Joey and Maria’s effort to help Charlie better manage his behavior. When Charlie begins acting out, Joey watches while Maria pleads with him. As Joey gets frustrated with the ineffectiveness of Maria’s pleading, he begins to threaten Charlie that they will go home if he doesn’t straighten out. Maria, anxious to avoid a scene, responds with further pleading, which invites further threats from Joey. This interaction undercuts each parent’s efforts and constrains their ability to more effectively parent together. Their parenting is further hampered by Maria’s family’s dismay at Charlie’s behavior. As Maria’s mother becomes more judgmental, the foster parents become more tentative which invites increased judgment. The cumulative effect of these patterns constrains Joey and Maria from effectively supporting Charlie in managing his behavior.

At a social network level, there is a constraining interaction between the protective services worker Pam, and Maria in which Maria feels lied to and not supported by Pam around Charlie’s abuse disclosure, who in turn sees Maria as exaggerating Charlie’s difficulties. The more Pam minimizes Maria’s concerns, the more Maria maximizes her frustrations; the more Maria expresses her frustrations, the more Pam views Maria as a “problem” and dismisses her concerns, and on and on.

Finally, at a socio-political level, we can identify a number of ways in which gendered beliefs support particular family interactions and constrain alternate possibilities. Maria’s pleading and Joey’s threatening are embedded in their respective ideas about being a woman and a man and cultural ideas about men’s and women’s roles and power in relationships. Consider Joey’s statement, “I hate it when Charlie doesn’t listen to his mother. I can’t just sit by and let him do that to her.” When asked about that statement, he replies, “What kind of man would I be if I just sat back and let her take that.” This response is strongly influenced by broader cultural ideas about how men, women and children “should” be and act. Examples of such ideas include “men should be in charge,” “men should protect and rescue their women,” and “children should be seen and not heard.” These ideas can be seen as cultural specifications that encourage particular ways of being and discourage others. Often they are unspoken but extremely powerful. They specify normative roles for men and women and construct anyone who lives outside those specifications as abnormal (Freedman & Combs, 1996b). In that sense, they constrain alternative possibilities.

Another example of the constraining influence of taken-for-granted cultural assumptions is the way in which Maria experiences significantly more judgment than Joey from her family. She says, “Joey doesn’t notice, but when Charlie starts acting out, I can feel their eyes on me. It’s not enough I couldn’t have my own kids, now I can’t even manage this one.” This statement is embedded in strong premises that evaluate Maria’s adequacy as a woman in terms of her ability to conceive children and manage them. These premises in turn, are embedded in cultural ideas about Maria’s role as a woman and mother. For both Joey and Maria, these broader cultural ideas both shape and constrain their options.

DISCOURSE AS A WAY TO UNDERSTAND CULTURAL INFLUENCES

Numerous authors have suggested the usefulness of “discourse” as a way to examine the influence of our broader culture on individuals and families. Rachel Hare-Mustin (1994, p. 19) defines discourse as a “system of statements, practices, and institutional structures that share common values.” In this definition, discourse includes our taken-for-granted cultural assumptions (e.g. in Joey’s and Maria’s situation, the cultural “truths” that “men should protect their women” and “a mother is responsible for her child’s actions”), our unexamined daily habits (e.g. Joey steps in to discipline Charlie when he talks back to Maria and Maria apologizes to her mother when Charlie misbehaves) and the economic, political and cultural institutions within which these assumptions and actions exist. These are all intertwined and we both participate in and are the recipients of them. Taken-for-granted cultural assumptions about men’s and women’s roles shape how Joey and Maria interact when Charlie misbehaves. In turn, their interactions around his misbehavior maintain those prevailing gender assumptions.

Discourses can be seen as “presumed truths” that are part of the fabric of everyday life and become almost invisible. They are difficult to question, shape our identity, and influence attitudes and behaviors. In our lives, we are subjected to multiple and often conflicting discourses. However, over time, certain discourses become dominant and take up more space in our culture. Discourses are often prescriptive, and include cultural specifications about how people should be and against which people compare themselves. They both reflect the prevailing social and political structures and tend to support them. Michel Foucault, a French social philosopher, examined the way in which cultural discourse is internalized by individuals. He suggests that people monitor and conduct themselves according to their interpretation of cultural norms (Foucault, 1980). Through this process, discourse shapes our sense of who we are and who we “should” be. When cultural discourses become a framework for making sense of our lives, those experiences that do not fit become invisible. This process has marginalizing effects on some individuals and families. Their own knowledge is obscured and their life is interpreted through the lens of dominant discourses. In this way discourse contributes to the construction of identity and constrains alternative possibilities.

THE CONSTRAINT, NOT THE PERSON, IS THE PROBLEM

The family just described highlights interlocking constraints at multiple levels. Anchored in a theory of constraints, therapy can become a collaborative effort in which the therapist works with the family to help them identify and address the constraints in their lives. In Charlie’s family, constraints included Charlie’s possible attentional difficulties at a biological level (“hyperness” as they called it), Charlie’s mistrust and suspiciousness at an individual level, a threatening/pleading interaction between Joey and Maria at a family level, a minimize/maximize interaction between Maria and the protective worker at a social network level, and the influence of gender discourses at a socio-cultural level. We can think about each of these constraints as a distinct entity separate from the people involved rather than viewing the constraint as part of the person or family. This conceptualization opens space to examine the relationship between the family and the particular constraint. At times it is helpful to personify problematic constraints. For example, we could think about hyperness (or mistrust or suspicion) as an entity that has come into Charlie’s life and now wreaks havoc. We can then think about Charlie as being in a relationship with hyperness (which wreaks havoc in his life) rather than being hyper or having an attention deficit disorder. The process of talking with clients in this way is referred to as “externalizing conversations.” This profound shift in thinking about problems was originally developed by Michael White and David Epston (1990) and has been subsequently elaborated by many others within the narrative therapy community. Externalizing conversations consist of questions that move from the internalizing language of clients (e.g. I’m depressed and bring this misery on myself) to externalizing questions (e.g. What does depression get you to do that you might otherwise not prefer?). Externalizing is not simply a therapy technique but a way of organizing our clinical thinking. It offers a way to separate (in our own minds) persons from the problems in their lives. From this perspective, the person is not the problem, the problem is the problem. This conceptualization organizes our thinking differently. The goal is to separate people from problems in order to challenge ways of thinking that are blaming and unhelpful, and to open ways for people to experience their association with a problem as a relationship with the possibility of developing a different, preferred relationship with that problem.

We can also externalize constraining interactions and beliefs. For example, the threatening/pleading interaction between Joey and Maria can be thought of as a pernicious pattern that gets hold of them and significantly interferes with their joint parenting. Likewise, the prevailing cultural belief that “men should protect their women” and a “mother is responsible for her child’s actions” can be seen as separate from Joey and Maria and taking a significant toll on their sense of self. This way of thinking is radically different from our traditional internalizing assumptions (he is schizophrenic or he has schizophrenia) that locate problems in individuals and is often difficult to incorporate. However, this way of thinking can be extremely useful. It offers a way to disentangle blame and responsibility (which are so tightly intertwined in our culture). If we think about problems, interactions and beliefs as separate entities that take a toll on clients, we can avoid blaming clients for the difficulties in their lives. This approach positions us in a different relationship with clients. At the same time, thinking about clients as being in a relationship with problems allows us to examine both the problem’s influence on them (which avoids blame) and their influence on, resistance to, or coping with the problem (which promotes responsibility from a supportive rather than demanding position). The use of externalizing conversations to simultaneously avoid blame and invite responsibility will be explored in depth in Chapter 5.

The shift to a conceptual model based on constraints in which individuals are seen as distinct from those constraints has a number of advantages. By shifting from causes to constraints, we orient ourselves to context as well as internal qualities and thus expand our unit of analysis. By seeing people as distinct from and more than the constraints in their lives, we open space to connect with them as human beings and appreciate their resourcefulness in addressing constraints. Finally, this focus can unite therapists and family members as they struggle together against constraints rather than against each other. This focus invites a stance of solidarity in which our task with clients becomes identifying constraints and then standing with them to support and assist them in challenging those constraints.

This section has focused on constraints across multiple levels. We can also think of constraints as existing in realms of action (interactional patterns) and meaning (beliefs and life stories). To pursue this distinction in more depth, let’s now examine ways to better understand constraints in realms of action and meaning.

CONSTRAINTS IN A REALM OF ACTION

People’s actions are often embedded in interactional patterns that constrain alternate possibilities. One of family therapy’s great contributions to the field of mental health has been the shift from focusing on individuals to focusing on interactions. However, we can take that shift even further and begin to view the people caught in such patterns as distinct from those patterns. One organizing schema that is particularly useful for distinguishing and externalizing interactional patterns was developed by Karl Tomm (1991). Rather than diagnosing individuals, Tomm sought to diagnose what he refers to as pathologizing interactional patterns or PIPs. This section draws heavily on his organizational system.

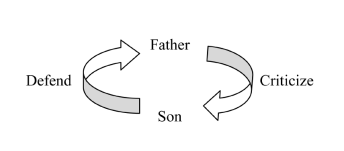

Over time, the ways in which people interact repeat with some regularity and develop into a pattern. Patterns of interaction have a major influence on individual experience and mental health. Some patterns can help us feel competent and connected to others. For example, every time Jane brings home a test with a B, her father compliments her on her effort and she responds by asking for help with the questions she got wrong. His compliments make it easier for her to ask for help, and her requests for help make it easier for him to compliment her. In the interaction, both feel competent and connected. Other patterns can help us feel incompetent and disconnected from others. For example, every time John brings home an A-, his father chastises him for not getting an A. John responds by declaring that school doesn’t mean anything anyway, which confirms for the father that he’s not working hard enough. The father’s criticism invites the son’s defensiveness, and the son’s defensiveness invites further criticism. The outcome of the sequence leaves both John and his father feeling incompetent in their respective roles as student and father, and disconnected from each other. The effects of patterns depend on the nature of the actions and the meanings attributed to them. In the second example, the effects of the interaction on John would depend on how his father criticized him and what meaning the boy made of his father’s criticism (e.g., the effects of his father’s criticism would be quite different if John saw it as confirmation that he just wasn’t good enough than if he simply saw his father as an old perfectionist who can’t help himself).

Interactional patterns can be seen as a series of mutual invitations in which the actions of one person invites a particular response from the other and the response in turn invites a counter response. In the previous example, the father’s criticism invites the defensiveness on John’s part. John’s defensiveness (“School doesn’t mean anything anyway.”) in turn invites further criticism from the father (“See, you’re not taking your studies seriously.”), and on and on. Over time, these patterns can take on a life of their own and induct participants into them. John and his father each “know” the other’s response before they even hear it. As the pattern becomes stronger, it develops into a major organizing component of their relationship and has significant influence over their experience of each other and their relationship. The pattern could be diagrammed as follows:

In examining this interaction, it is important to acknowledge that the participants do not have equal opportunities to contribute to the interaction. Although both the father and son contribute to this interaction, their participation and influence in the interaction is not equal. Fathers (as a cultural group) have more power and influence than sons (as a cultural group). Preexisting power differences bias participation and need to be taken into account. As a result, these diagrams are organized with the father placed vertically above the son to remind us of the broader cultural power relations.

THE PATTERN, NOT THE PERSON, IS THE PROBLEM

Focusing on the pattern rather than simply the people involved represents a fundamental shift in perspective. In this shift, we are moving from diagnosing and labeling people to diagnosing and labeling patterns. As we separate the pattern from the family members caught up in it, we can focus on the pattern rather than the person as the problem. From this perspective, the family is not doing the pattern; rather, the pattern is doing them. The pattern can be seen as separate from the persons captured by it and having strong effects on them. At the same time, the people caught by the pattern are not passive victims of the pattern. While the pattern may pull them into it, they have opportunities to resist that pull and often have numerous experiences with each other outside of the pattern. Our work can focus on eliciting and elaborating those experiences outside the pattern as a foundation for resisting the pull of the pattern.

SOME EXAMPLES OF CONSTRAINING PATTERNS

Karl Tomm (1991) and his colleagues have distinguished over 200 specific PIPS that generate or support common problems. Similar patterns have also been described elsewhere (Cade & O’Hanlon, 1993; Madsen, 1992; Watzlawick, Bavelas, & Jackson, 1967; Watzlawick, Weakland & Fisch, 1974; Zimmerman & Dickerson, 1993). The following are examples of interactional patterns that often constrain effective management of problems faced by multi-stressed families. I will briefly describe several patterns to highlight the shift from locating problems in individuals to locating problems in patterns and then address the usefulness of this schema for addressing patterns.

Over-responsible / Under-responsible

Jim is a stubborn, independent old guy who smokes like a chimney and insists that his chronic lung disease is not a problem. A retired assembly-line worker, he describes himself as a “hardworking guy who just ran out of gas and retired.” Given his family history of early deaths, he sees himself as “more or less living on borrowed time” and accepts his situation fatalistically. He doesn’t let things bother him and his attitude toward life is visible in the wry smile that accompanies his persistent refrain “The rain’s gonna fall, nothing to do about it.” His wife Chris, also a smoker, is very worried about his medical condition. She left her family-of-origin role as a caretaker to become an emergency medical technician and is proud of the fact that “no one has ever died on her watch.” After Jim’s forced retirement due to health issues, she took on his medical condition as a project, minimizing her own health concerns. However, the harder she tries to get him to stop smoking, the more he smokes, and the more he smokes, the harder she tries to get him to stop. We could make sense of this situation in a number of ways. Jim could be seen as “in denial” about his medical condition or Chris could be seen as “codependent,” using her husband’s health crisis to conveniently avoid her own issues. We could also focus on the interactional pattern between them that constrains effective management of his medical condition. Jim’s under-responsibility for managing his medical condition invites Chris’ over-responsibility. As she puts it, “I have to nag him about smoking because he won’t take it seriously.” Chris’ over-responsibility for the management of his medical condition invites Jim’s under-responsibility. In Jim’s words, “She worries enough for both of us. Why should I add to that?” Paradoxically, the interactional pattern rigidifies Jim’s stance that his smoking is not a problem and constrains his management of his medical condition.

Minimize / Maximize

Mary is a 43-year-old teacher who suffers from progressive kidney disease and deteriorating eyesight due to unmanaged diabetes. She hides her medical problems from her Christian Scientist parents who she thinks view illness as a weakness of character. She lives with her husband Bruce (45), and their three children. There have been numerous crises in the family over the years, and Mary, in her role as family manager, has had little time to focus on her own medical condition. When she does, she alternates between obsessively worrying about her declining health and berating herself for being out of control. Bruce’s concerns about her medical condition are eclipsed only by his fears about her pessimistic attitude, which lead him to continually encourage her to be more optimistic. When Bruce, distraught about her pessimism, tells her she’s got to be more positive, Mary responds, “What’s there to be positive about? The only thing that’s positive is that I’m gonna get sicker, I’m gonna need a kidney transplant, and I may die.” Bruce, as a Pop Warner football coach, tries to tell her that with that attitude, she’ll never win the game and she responds with, “Oh you want optimism, how about this. The good news is when I lose my kidneys, I’ll have already lost my eyesight, so I won’t have to watch the gruesome scene.” This of course, confirms Bruce’s belief that she needs an attitude transplant. Bruce’s attempts to help her are experienced by Mary as minimizing her concerns (e.g. “it’s not that big a deal, just get a better attitude”) which invites her to respond by maximizing her concerns (“you don’t realize how bad it is, let me explain it to you”) which invites more minimizing (“now honey, get a grip, you’ll never win the game with a losing attitude”). As the sequence unfolds, both Mary and Bruce feel increasingly misunderstood and compelled to state their case more strongly. In the process Mary is continually emphasizing how little control she has over her medical condition. In this way, the pattern rigidifies her stance that her medical condition is beyond her control and constrains effective management of it. When describing sequences such as this, it’s common to describe the reaction to the “identified patient” first in an attempt to move from focusing on the individual to focusing on the interaction. This is not meant to imply the pattern starts with minimizing. Such a pattern could also be described as maximize / minimize.

Susan and Richard are an upper-middle-class white couple who both work and share parenting responsibilities for their two children. Each morning at breakfast, Richard reads the newspaper, while Susan tries to talk to him about their plans for the day while also getting the kids ready for school. At night, when work is over and the kids are asleep, Susan wants to talk about their respective days, while Richard wants some down time after a stressful day at work and would rather watch his favorite sports team on TV. Periodically, Susan complains, “We never talk anymore.” Richard feels backed into a corner and doesn’t know how to respond. He retreats into his newspaper or sports, and Susan, feeling increasingly alone in the relationship, tries various ways to connect with him. The more she pursues him, the more he withdraws and the more he withdraws, the more she pursues. The pattern organizes the responses of each and their actions intensify the pattern. While focusing on the pattern allows us to shift away from locating the problem in individuals, it is also important to take the broader cultural context of the pattern into account and acknowledge the ways in which gender roles and expectations contributes to the construction of this pattern.

Demand disclosure / Secrecy and Withholding

Denise is an African-American 12-year-old, brought to therapy by Yolanda, her single-parent, working-poor mother, after Denise was arrested for shoplifting. Yolanda is irate about her daughter’s arrest and the fact that Denise keeps lying to her. Yolanda worries about the prevalence of gang activity and drugs in their inner-city neighborhood and keeps a tight rein on her daughter. Denise is furious that her mother doesn’t trust her more and periodically sneaks out at night to “get some space.” She’s spending more and more time locked in the bathroom, the only private room in their apartment; and Yolanda is very worried about what she’s doing in there. However, the more Yolanda demands answers, the more Denise clams up and tells her mother to get out of her face. Denise’s secrecy drives Yolanda crazy and sends her into a flurry of accusations and interrogation. Yolanda’s interrogations reciprocally enrage Denise who experiences them as statements of mistrust and responds by refusing to answer them. The shift to a focus on the pattern rather than the individuals holds the potential to depersonalize and de-escalate their interactions.

Correction and control / protest and rebellion

Bart Jr. is a 12-year-old working class white boy who has been brought to therapy by his single parent father who is fed up with his son’s absolute refusal to respond to limits. Bart Sr. describes himself as “growing up in a rough neighborhood, falling in with the wrong crowd, and doing time in prison as a young man before seeing the light and turning his life around.” He has vowed that his son will not repeat his same mistakes and keeps his son on a very strict regimen of chores and studying in an attempt to keep him away from bad influences. However, the more chores assigned to Bart Jr., the more he refuses to do them and the more he refuses to do the chores, the longer the list of demands on him grows. Another less extreme version of this pattern is reflected in a conversation between my preteen daughter and I that has become a running joke between us. The conversation goes, “Arlyn, you need to clean your room.” “Dad, if you got off my back, I’d clean it.” “Arlyn, if you’d clean it, I wouldn’t be on your back.” and on and on.

ADDRESSING INTERACTIONAL PATTERNS

This shift from assessing people to assessing patterns holds significant advantages. It allows clinicians to make sense of families in ways that objectify patterns rather than individuals. It positions clinicians in a different relationship with families, inviting more compassion and empathy, and minimizing judgment and blame. It helps families to resist self-stigmatization and to join together against the pattern rather than against each other. It also creates space for them to distance themselves from the pattern and develop a new relationship to it. Finally, a focus on patterns implies directions for intervention. For example, in the overly harsh / overly soft sequence, we could, from a structural family therapy perspective, set up an enactment in which the therapist invites either party to shift his or her response as the pattern is played out in the session. The therapist could ally with the mother and unbalance the couple in an attempt to shift the pattern. From a strategic family therapy perspective, a therapist could prescribe and exaggerate the pattern in an attempt to disrupt it. From a solution-focused perspective, the therapist could inquire about exceptions in which the couple’s stances are less polarized or when their responses support each other. And, from a narrative perspective, one could externalize the pattern, examine the effects of the pattern on the husband, wife and their relationship, examine the ways in which cultural discourses coach the father and mother into those patterns and support them in their development of preferred patterns which would contribute to a restorying of their relationship in a preferred direction. The particular approach chosen will depend on the therapist’s theoretical orientation, but this categorization schema has heuristic value across orientations. It provides a concise model for assessing patterns that reinforce particular ways of interacting and constrain alternatives. Once these patterns have been clearly described, strategies for addressing them follow fairly easily.

In each of these situations, the pattern could have been described in a number of ways. There is significant overlap between these patterns. It’s important to note that these patterns do not represent real, objective facts but, rather, distinctions drawn by the therapist. In this sense, this taxonomy of pathologizing interpersonal patterns is no more real than the traditional Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) used to diagnose individuals. Any assessment or formulation consists of distinctions drawn by the worker. The important question becomes how useful are they and what are the consequences of using them? For example, what are the effects of thinking about a family this way? How does it help us to understand them and guide us in our work with them? What view of them does it give us? What is the impact of that view on our relationship with them? Does this formulation invite respect, connection and curiosity or does it invite disrespect, distance, and judgment. A number of patterns are highlighted here to help orient the reader toward possible patterns, however, in distinguishing these patterns it is important to construct them with families, drawing on their language. Otherwise we run the risk of debating among ourselves which is the real pattern and then imposing that description on the family.

CONSTRAINTS IN A REALM OF MEANING

We can also distinguish constraints in a realm of meaning. The beliefs we hold constrain us from alternative possibilities. Potentially constraining client beliefs that are worthy of consideration include beliefs about the problem, beliefs about treatment (or what should be done about the problem), and beliefs about roles (or who should do what about the problem) (Harkaway & Madsen, 1989; Madsen, 1992). Within these three broad areas, we can identify a number of important questions. Relevant beliefs about the problem include the following:

- Is this a problem? For whom? In what way?

- How did this come to be a problem?

- Does the client have any control over the problem?

- Are there any special meanings associated with the problem?

These questions are sequential because the answers to each question profoundly affect the framing of subsequent questions. For example, if the “problem” is not defined as a problem, then the question of client influence over the problem is irrelevant.

Is this a problem, for whom and in what way? If a client does not view what appears to us to be a problem, it makes sense that they may not be invested in addressing that problem. Jim, the smoker with chronic lung disease did not view his smoking as a problem. He did, however, see smoking as a problem for his wife (because she was “still young and healthy”). Jim would be willing to stop so that his wife would get off his back and address her own smoking. Knowing this belief allows us to shift our efforts and engage Jim around quitting to help his wife’s health (which generates more interest for him) than to improve his own health.

A second question is How did this come to be a problem? The way in which family members view the evolution of a problem profoundly shapes their attempts to manage the problem and their expectations of treatment outcomes. For example, Thomas misbehaves. His mother views his restlessness and behavioral difficulties as signs of an undiagnosed attention deficit disorder and seeks medication for him. The psychiatrist that they go to see is ambivalent about prescribing medication in this instance, but goes along with the mother’s request. Later he learns that the mother never filled the prescription. Initially, annoyed with her noncompliance, he decides to investigate the situation further. He calls their home and when the father answers, finds out that the father, who is adamantly opposed to medication, threw out the prescription when the mother brought it home. The father views Thomas as a spoiled brat and contends that Thomas just needs some limits set on him. The parents’ differing views of the etiology of Thomas’s behavioral difficulties lead them to different preferred treatment protocols (medication for a biological problem vs. consequences for a behavioral problem). Paradoxically, the way in which they manage their different opinions constrains their attempts to parent together. The psychiatrist schedules an appointment with the parents and, taking some time to enter into their respective views of the evolution of this problem, develops a better appreciation for their respective beliefs. From within their logic, he emphasizes the importance of a containing environment to help manage a potential biological problem and the way in which medication may help Thomas better respond to limits. The parents develop a mutually acceptable plan for dealing with their son.

A third question is Does the client have any control over the problem? Donna was a single parent mother of four strapping adolescents who drank heavily and terrorized the neighborhood. Donna grew up in an alcoholic household and was repeatedly abused by her father until she left home, marrying a man who later came to periodically rape and batter her when he was drunk. When he abandoned the family, she was left to raise four large adolescent boys who scared both her and the neighborhood. Attempts to get her to set limits on the boys and hold them accountable for their actions devolved into a minimize/maximize sequence in which the therapist’s plans for consequences were repeatedly met with a litany of the boys’ infractions. When the therapist addressed Donna’s belief that she had no control over her boys and shifted to the effects of her multi-generational story of victimization on her parenting, Donna began to identify times when she didn’t feel completely victimized by her sons’ actions and used that as a foundation to begin to demand that they at least treat her with respect in her house. That demand represented an important first step in their development of accountability.

A fourth question is Are there any special meanings associated with the problem? Often problems carry with them issues of family membership and loyalty, for example “All the boys in the family have done time in juvenile hall,” or “He’s just like Uncle Joe.” The following situation highlights another example of special meanings of problems. Mark was having difficulty finishing high school when his father’s sudden death threw the entire family into a panic. Mark became very depressed and was hospitalized. At the hospital, he complained of vague hypnagogic hallucinations as he was falling asleep where he would have visions of his father, which terrified him. He was prescribed an antipsychotic medicine which he refused to take. His family’s support of this stance precipitated significant conflict between the family and the hospital staff. However, this decision became understandable in the context of a long family history of having conversations with dead relatives and seeking their advice. The boy needed his father’s advice about surviving his death and graduating high school and feared that the medication would take his father away yet again. Within this context, Mark’s resistance to medication becomes more understandable. When a consultation interview elicited the special meaning associated with Mark’s “visions,” the psychiatrist was able to discuss with Mark and his family ways in which medication might be able to take the edge off his conversations with his father without eliminating the possibility of such conversations and the family’s resistance to medication eased.

We can also frame questions about beliefs about treatment. The first question is Is treatment effective? or Can something be done about this problem? I used to consult to a large public hospital and met with Samuel, a 70-year-old African-American man with chronic hypertension. Partway through a consultation, he turned to the resident working with him and said, “You know son, I’ve been coming here for 30 years, and each year I get one of you young fellows telling me to take these pills and stop eating salt. Salt ain’t got nothing to do with my tension and these pills ain’t nothing but sugar. I’m old, but I ain’t a dead horse, so when you gonna stop beating your head against me?” When the resident heard this, he realized the futility of prescribing a treatment that only he believed useful. He began to inquire about Samuel’s belief that hypertension medication was not useful and learned that he only took it when he got heartburn. The physician continued to ask Samuel what he thought should be done about hypertension and learned a wealth of interesting folklore and alternative treatments. Out of a discussion about their respective beliefs, a joint mutual respect and trust emerged that allowed Samuel to give the medication a chance, even though he was skeptical. Repeated experiences of treatment failures may contribute to a belief that treatment isn’t effective. Understanding such a belief makes a client’s unwillingness to pursue a particular course of action understandable and may suggest different ways of framing suggestions.

A second question is What is the most appropriate treatment? or What would be the best thing to do about this problem? Clients’ explanations of the problem and their views about its etiology profoundly affect their ideas about how the problem should be addressed. As we saw in the example of the mother and father who disagreed over the cause of their son’s misbehavior, different family members may hold divergent beliefs about what should be done about a problem. Conflicts over the “appropriate” treatment may constrain effectiveness and polarize the participants, inadvertently rigidifying each person’s position. Understanding clients’ beliefs about treatment allows us to work within clients’ logic which is often more effective.

Finally, we can identify beliefs about roles or who should do what to address the problem. We can identify beliefs about Who in the family should do what. In the family discussed previously, the parents not only disagreed about what the treatment should be (medication or limit-setting), but also roles. The father thought the mother should provide more discipline, the mother thought the father should get more involved with his son and fill the prescription. It is also useful to explore family beliefs about the role of the family and the role of the professional. Some families may think it is more appropriate to handle a situation themselves than ask a professional who is an “outsider and doesn’t know our child the way we do.” It is important that we not move in too quickly in our attempts to be helpful. We are better positioned when we first obtain an invitation to help before proceeding. However, the process of getting such an invitation is not a time-consuming, passive process. We need to actively work to get invited in to help. Chapter 3 on engaging reluctant families outlines concrete, active steps to accomplish this task. At the other extreme of beliefs about roles, some families may feel profoundly disempowered and believe they should place their child’s care in the hands of an expert who will take charge. The mother with four strapping adolescents continually looked for a therapist who would successfully tell her boys to stop being rowdy. At the same time, she didn’t trust that anyone could really help and found herself continually second-guessing every helper involved with her family. In the context of her history, that combination of personal disempowerment and protectiveness for her boys becomes very understandable.

In medicine, it is considered unethical to prescribe a medication without knowing some basic biological facts and what other medications a patient is taking. It is important to have a full understanding of the receiving context into which a medication is introduced as well as be aware of it’s potential interaction with other medications. Likewise, in psychosocial interventions, it is important to fully understand the receiving context and potential interaction effects between therapist interventions and client meaning systems. Assessing client beliefs about problems, treatment and roles helps us to do this.

MEANING AND CLIENTS’ LIFE STORIES

As we focus on constraints in the realm of meaning, we can also examine the constraining effects of personal narratives or life stories. A narrative approach begins with a belief that people are interpretive beings continually trying to make sense of their experiences in life. Human beings organize their experiences in the form of stories (Bruner, 1990). Life stories provide frameworks for ordering and interpreting our experiences in the world. At any point, there are multiple stories available to us and no single story can adequately capture the broad range of our experience. As a result, there are always experiences that fall outside of any one story. However, over time particular narratives are drawn on as an organizing framework and become the dominant story. These dominant stories are double-edged swords. They make our world coherent and understandable and yet, in the words of White and Epston (1990), “prune, from experience, those events that do not fit with the dominant evolving stories that we and others have about us” (p. 11). Narratives organize our field of experience, promoting selective attention to particular events and experiences and selective inattention to other events and experiences. In this way, much of our lived experience goes unstoried, is obscured, and phenomenologically does not exist. Particular narratives can become problematic when they constrain us from noticing or attending to experiences that might otherwise be quite useful to us.

We can refer back to Charlie, Maria, and Joey for an example of this process. Maria described growing up as the “lost child who could never quite measure up” in her family. Her two older brothers were encouraged to make something of their lives in the United States by their Italian immigrant father. Her older sister was considered eccentric and Maria took care of her two younger sisters who were considered quite gifted. Maria grew up in a very traditionally gendered household. Her father worked hard and was seldom home. Her mother worked at home as a housewife and devoted herself to the children. Maria developed a strong internalized voice that “a mother’s life is her children.” This voice received significant support from her family of origin, her ethnic culture, and dominant cultural ideas about the role of women in families. Maria was the first to marry and her parents eagerly awaited grandchildren. When she found out she was unable to bear children after years of unsuccessful attempts, shame kept her from telling her mother for 2 years. When she finally told her mother, the mother wept uncontrollably for 3 days. Maria blamed herself for this effect on her mother, which only enhanced her shame and strengthened her story of “not measuring up.”

Charlie entered Maria and Joey’s life as an explosion of joy. However, that joy was shattered when he disclosed sexual abuse in a previous foster home. Once again, Maria felt lost, unable to measure up, shamed, and isolated. As Charlie began “not measuring up” at school and in Maria’s family of origin, she feared he was scarred for life. This story of not measuring up and being a victim to lifelong scarring resonated for her and led to incredible despair for Maria in thinking about both Charlie’s plight and her own.

This story of “I’m alone and I can’t measure up” organized Maria’s experience of herself and of Charlie. It led to great distance from her husband who worried that she was slipping away from him. Maria’s understanding of her life was filtered through this story. Those events that fit were reinforced. She was acutely aware of her family’s response to Charlie’s misbehavior. She was furious with Pam (the protective worker) for her lack of availability to Charlie and the family, and she was in a pitched battle with the school over their scapegoating of Charlie. However, the events that fell outside the story of “I’m alone and can’t measure up” were rendered almost invisible. Maria was a wonderfully competent parent to Charlie. She was adept at sensing his needs and had a deep connection to him. Her home was the first place he felt secure enough to disclose the abuse. She had two friends who marveled at how she parented Charlie (a fact she minimized until the two friends were brought into sessions). And yet, within her life story, there was no way to make sense of these experiences.

Much of our work with families can focus on helping them to challenge the constraining effects of dominant life stories by inviting them to attend to events that fall outside those stories as a foundation for constructing new stories within which to interpret their lives. For example, as the therapist elicited Maria’s experiences of competent parenting and her thoughts about those instances, Maria began to organize her perception of herself and her life in a radically different fashion. As her two friends were asked to comment on those instances of competence, the emerging threads of a new story could be woven together in a tighter, more complex pattern. A colleague of mine once described that process as “shining a light on instances of competence and asking clients what they notice.” Concrete clinical practices to invite this process are further examined in the latter half of this book.

Returning to the constraining effects of dominant life stories, the phenomenological disappearance of instances of competence from Maria’s life raises a question of how the story of “I’m alone and can’t measure up” developed and how other events in Maria’s life were “pruned from experience.” To address this question, we need to return to an examination of the internalization of cultural discourses and consider the ways in which broader cultural narratives constrain the development of an alternative story that might bring Maria’s connection and competence to the fore.

THE SOCIO-CULTURAL CONTEXT OF LIFE STORIES

The stories that shape our lives are not simply our own. In many ways, they are received from and embedded in family and cultural stories that organize our sense of self and our relation to the world. Stephen Madigan (1997) quotes feminist author Jill Johnson (1973) who claims “identity is what you can say you are, according to what they say you can be” p. 18). The “they” in this case, refers not to particular individuals, but to cultural assumptions and practices passed on through those around us. As described earlier, cultural discourses are internalized by individuals. Weingarten (1998) describes internalized discourse as “the kinds of self-statements that can be produced by incorporating dominant cultural messages” (p. 9). These self-statements are comparative and evaluative, filled with shoulds and oughts. We all live with internalized discourses and they usually leave us believing that we, just like Maria, have not measured up to them.

Maria’s story that she couldn’t measure up or look to others for assistance is shaped by cultural shoulds and oughts for women in our culture. Her sense of being defective because of her inability to bear children and then her anticipated adoption of a “broken” child is embedded in a cultural story that often equates womanhood with motherhood and a family-of-origin story that a “mother’s life is her children.” Women are encouraged in our culture to take care of others and regard their own needs as secondary (Bepko & Krestan, 1990). Within that cultural idea about how women should be, bothering her husband or her friends with her troubles was an unthinkable option for Maria. She couldn’t impose on others and yet was furious at feeling so alone and unsupported. She had no way of making sense of that fury and it confirmed for her that she didn’t measure up as a good wife or mother.

Throughout the stories we hold about ourselves, we find repeated examples of the influence of our broader culture. Gender, race, class, and culture permeate our everyday life. Problematic interactional patterns and belief as well as constraining life stories are embedded in cultural specifications or ideas about who we should be that are taken for granted and go unexamined. These cultural specifications often support problems in people’s lives.

In this way, we can see these cultural shoulds and oughts as separate from the people affected by them and again locate the problem in discourse rather than in individuals. Putting constraints in a broader cultural context has a number of effects. It alleviates blame and shame, it counters isolation (e.g., We are not the only ones struggling with this; maybe it’s not simply about our inadequacies), it allows the emergence of personal agency to resist constraints, and it counters the invisibility of cultural specifications by naming them. Placing constraints in a cultural context also enriches our understanding of the fabric of clients’ lives. Such an endeavor allows us to develop stronger conceptual understandings of clients and families and to intervene more effectively on their behalf. A broader understanding of clients’ context also helps us to connect to them in more humane ways.

RECURSIVENESS OF ACTION AND MEANING

This discussion of constraints has separated out realms of action and meaning. However, they are actually complexly interwoven. The way in which we make sense of the world profoundly influences how we interact in it, and our interactions, in turn, either support or challenge our beliefs. We enact or play out the stories we hold about our lives. In the process, we invite others to participate in the performance of our life stories. Their participation shapes those life stories. The ways in which others respond may either confirm or challenge our life stories. However, at the same time, others’ actions are interpreted within the predominant story. As a result, actions that fall outside that narrative may not be noticed.

As helpers, we are often invited to participate in the enactment of existing family narratives, and the way in which we respond to that invitation can have a profound effect. In fact, we are often simultaneously invited into several possible family narratives, and we can respond by noting the range of possible narratives into which we have been invited and selecting which ones we will respond to and in what ways. Our interactions with clients can inadvertently invite the enactment of pathologizing and constraining life stories. Our interactions with clients can also invite the enactment of healing and empowering life stories. Those interactions are shaped by the way in which we enter them and reflects a choice on our part. However, our interactions with clients are influenced by our conceptual models and, in many contexts, channeled through the assessment process.

EXAMINING OUR ASSESSMENTS

As highlighted previously, the need for writing assessments in most agencies is a taken-for-granted fact of life. As we have seen, assessments are also interventions. As such, it is important to examine the effects of both the content and process of our assessments. The most frequent misuse of assessments is when they become a laundry list of all the things that are wrong with clients. Ironically, the field of mental health has been much better at emphasizing illness than health. We have many more tools for discovering how things went wrong with clients than for identifying steps to help them do better in their lives. If assessments are to be an effective guideline for therapy, we need to understand problems in ways that are non-blaming and non-shaming, and we need to promote particular attention to the strengths and resources possessed by families. If we think about problems as ruts in clients’ lives, a strengths-based focus helps us not to become further mired in the rut. Promoting particular attention to family competencies and knowledges helps us to identify the quickest way out of the rut. This section examines the effects of the content of our assessments and leads into an assessment outline that attempts to address some of the concerns raised. That outline follows with a discussion of the process of conducting assessments and a proposed framework that positions us as collaborators with families who together assess the problems in their lives rather than as experts who assess families.

Traditionally, our assessments are organized in a close approximation of the following sequence: Problem and Precipitant, History, Current Functioning, Medical Condition, Risk Factors, Mental Status, Formulation, and Diagnosis. We begin with the problem and its precipitants. We then go back to examine the history that led up to this problem. After examining current functioning and relevant medical information, we assess risk factors and mental status. Finally, we develop a formulation which leads to and justifies a particular diagnosis. Although this approach has a long history, I have a number of concerns about it. Briefly, the initial focus on the problem, precipitant, and history entrenches us in a problem focus. It promotes selective attention to pathology and dysfunction and selective inattention to health and competence. It organizes us around a search for causality and locates problems primarily in individuals. This framework organizes us to think in ways that run counter to the conceptual models proposed here. Developing formulations that justify a diagnosis runs the risk of simplifying and trivializing clients’ lives. Michael White (1997), expanding on the work of cultural anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1973), has drawn a distinction between thin conclusions and thick descriptions. Thin conclusions refer to the quick formulations we reach about clients that encapsulate their lives within our frameworks. Describing Linda as a “help-rejecting borderline” obscures the richness of her life. Likewise, simply describing her as “wonderfully resourceful” is also thin conclusion. Thick descriptions refer to the richly developed descriptions of people’s lives that incorporate many aspects of their lived experience and are anchored within their own meaning systems. We are pushed toward thin conclusions by many forces. Some examples include the obligation to diagnose, the pressure to do more with less resources, the demand to manage costs and increase productivity, and the requirement to demonstrate empirically valid, measurable outcomes. However, assessments can also be a vehicle for thick description. We can use them to develop richer understandings of clients’ lives. One way to use assessments towards this end is to develop formats that invite rich description rather than thin conclusions.

The traditional assessment outline is anchored in the medical model. Its continued use is encouraged by licensing and reimbursement regulations that mandate the inclusion of particular sections. The forms we use organize our thinking. To complete the forms, we need to ask particular questions. If we accept the assumption that the questions we ask generate experience as well as yield information, then assessment questions shape our experience of clients, clients’ experience of self and us, and structure our relationship in particular ways. The forms we use shape our interactions with clients in ways that contribute to their experience of self. This is not to say we are bound like automatons to forms and that the forms determine our interactions with clients. The forms we use invite us into particular interactions with clients and we can accept or decline those invitations. For a fine example of engaging in a post-modern practice within a traditional modernist context, I’d recommend Glen Simblett’s (1997) chapter on “Narrative Approaches to Psychiatry.” However, if we want our forms to support our work rather than simply meet bureaucratic requirements in documenting it, we can consciously develop forms that invite the ways of thinking about and interacting with clients that represent our preferred models and practices. The following assessment outline organizes our understanding of families in ways that support the ideas in this book. It is offered not as the way to conduct assessments, but as one example of various alternatives we could derive.

AN ASSESSMENT OUTLINE

The following assessment outline grew out of an endeavor to rewrite forms for a community agency that was integrating home-based and clinic-based therapy. Previously, the agency had one set of forms for the home-based family therapy teams and a second set of forms for the clinic staff based on a medical model and driven by licensing and reimbursement regulations. This outline has been subsequently adapted by a variety of agencies. The suggested assessment outline is a modification of forms developed to conform to licensing regulations and yet encourage the enactment of conceptual ideas presented here. The outline is a generic form that can be used with some modification for children, adolescents, and adults and in both individual and family therapy, and it has been adapted by a variety of agencies. The distinction between individual and family therapy is an unfortunate one. It pushes us to define therapy in terms of who is in the room. If we consider family therapy as a way of thinking about our work rather than a modality of therapy, the distinction between individual therapy and family therapy begins to dissolve. In many ways, “family therapy” is an unfortunate term that runs the risk of arbitrarily limiting the relevant system of conceptualization to simply the family. It is important that we broaden our thinking beyond families to social networks and that we include the socio-cultural context of people’s lives in our thinking as well. The following outline has been profoundly influenced by the work of Alexander Blount (1987; 1991) and builds on an assessment form he developed. The outline of the form is followed by brief explanations of each section.

ONE ASSESSMENT FORMAT

Identifying Information

- Demographic information

Description of the Family

- Brief description of members of family network that brings them to life (attach genogram or eco-map)

- Living environment and recent changes in household composition

- Family hopes and preferred futures

Presenting Concerns

- Presenting concerns in the words of the referral source

- Client/family response to referral

- Client/family definition of their concerns (in rank order)

- Client/family vision of life when concerns are no longer a problem

Context of Presenting Concerns

- Situations in which problem(s) is most/least likely to occur

- Ways in which client and others are affected by problem(s)

- Client/family beliefs about the problem(s)

- Interactions around the problem(s)

- Cultural supports for the problem(s)

Family’s Experience with Helpers

- Client’s/family’s current involvement with helpers

- Client’s/family’s past experience with helpers

- Impact of past experience on view of helpers

Relevant History

- Multigenerational history related to important theme regarding presenting concern, constraining interactions, beliefs and life stories, and experience with helpers.

Medical Information and Risk Factors

- Status of physical health

- Suicide – Violence – Sexual Abuse; Neglect – Substance Misuse

Mental Status

- Effects of presenting concerns on concentration, attention, memory, etc.

Risk Factors and Safety Factors

- Suicide, violence, sexual abuse, neglect, substance misuse

- Personal, familial, and community abilities, skills, and knowledge that protect from risk and promote safety

- Individual and family preferences, intentions, and hopes that protect from risk and promote safety

Diagnosis

- DSM diagnosis if required (may also include client colloquial language)

- Ways in which client’s experience is different from standard description of that diagnosis

Formulation

- Include information that addresses biological, individual, family and socio-cultural factors.